Clemency for Edward Snowden Would Not Set a Dangerous Precedent

In fact, it sets no precedent at all: His singular leak justifies special treatment.

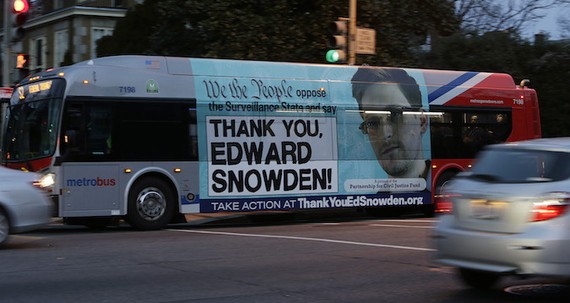

Some months ago, Edward Snowden wrote an appeal for clemency to the U.S. government, arguing that its “systematic violations of law" created "a moral duty to act.”

On New Year's Day, America's most influential newspaper officially agreed.

The New York Times editorial board dedicated one of its inaugural editorials of 2014 to the proposition that the former NSA contractor should be given a plea bargain or some other form of clemency. "Considering the enormous value of the information he has revealed, and the abuses he has exposed, Mr. Snowden deserves better than a life of permanent exile, fear and flight," the newspaper stated. "He may have committed a crime to do so, but he has done his country a great service."

The pushback was immediate. Josh Barro of Business Insider is among the editorial's smartest critics. He stated his dissenting position in a series of tweets late Wednesday. Here are a few of them:

This is nuts. Letting Edward Snowden off would set a terrible precedent that would encourage security breaches. http://t.co/mTRC0rPbaZ

— Josh Barro (@jbarro) January 2, 2014

"It's OK to violate your security clearance if you have a really good reason" is a terrible rule, even if some leaks are desirable.

— Josh Barro (@jbarro) January 2, 2014

@binarybits the question is: do you think it's good or bad if it becomes much harder for govt to keep secrets? My view is, bad, on net.

— Josh Barro (@jbarro) January 2, 2014

The case for clemency for Snowden is a radical case against our diplomatic and intel apparatus, which people make oddly casually.

— Josh Barro (@jbarro) January 2, 2014

Where this goes wrong is imagining that a plea bargain or some form of clemency (or even a presidential pardon) for Snowden would set a precedent or legitimize a general rule of any kind. It would not. The concepts of pardon and clemency are part our system precisely because there are instances when applying rules we've generally decided upon would be unjust and counterproductive. They are meant to be used judiciously, on an ad hoc basis, in what are clearly exceptional circumstances.

Snowden's leak meets those tests. Urging clemency for Snowden is not a radical case against our existing system of rules—it is an acknowledgment that, like all rules, ours are imperfect. One of the finest presidents, George Washington, pardoned farmers who took up arms against the federal government (!) to protest a tax on whiskey. He wouldn't have granted those pardons had he thought that he was making a radical case against the legitimacy of the U.S. government or setting a precedent for anti-tax insurrections. And it is difficult to argue that any such precedent was set, even at the dawn of the federal republic when norms were still being established.

Today, it is even more difficult to imagine that a pardon for Snowden, or one of the lesser forms of forgiveness the Times advocates, would cause other federal employees to imagine that they'd avoid punishment if, say, they made public the identities of American spies abroad or secret codes from the U.S. nuclear program. As a political matter, the fallout would be dramatically different. And it isn't as if plea bargains, grants of clemency, or pardons given to one man impose any sort binding precedent in the fashion of a Supreme Court ruling. In the unlikely event that forgiveness for Snowden caused anyone to start leaking other secrets, correcting the problematic "precedent" would be one swift prosecution away.

I trust that if the national-security state were drawing up a classified assassination list of American journalists even Barro would be amenable to a pardon for a federal employee who violated secrecy laws by leaking its existence to the press. He isn't opposed to forgiveness for any possible leaker—he just doesn't think Snowden in particular is worthy. So it seems to me that he doesn't just overstate the costs of a pardon for Snowden, he also neglects to acknowledge or address the unusually powerful reasons for granting one in this of all cases. When should a leaker of government secrets be forgiven rather than jailed? Here are some possible standards:

- When the leak reveals lawbreaking by the U.S. government

- When the leak reveals behavior deemed unconstitutional by multiple federal judges

- When a presidential panel that reviews the leaked information recommends significant reforms

- When the leak inspires multiple pieces of reform legislation in Congress

- When the leak reveals that a high-ranking national-security official perjured himself before Congress

- When the leak causes multiple members of Congress to express alarm at policies being carried out without their knowledge.

The Snowden leak meets all of those thresholds, among others.

There is a final weakness in Barro's argument. He treats clemency for Snowden as if it would meaningfully weaken norms against leaking classified information even though people in power leak classified information all the time without being punished for it. Jack Shafer made this vital point at length in a column published almost immediately following the first stories sourced to Snowden. "Without defending Snowden for breaking his vow to safeguard secrets," he wrote, "he’s only done in the macro what the national security establishment does in the micro every day of the week to manage, manipulate and influence ongoing policy debates."

The difference is that the constant leaks that serve those in power seldom get to the point where prosecution is considered. Indeed, they are seldom even noticed they happen so often. Shafer writes:

President George W. Bush’s administration declassified or leaked whole barrels of intelligence, raw and otherwise, to convince the public and Congress making war on Iraq was a good idea. Bush himself ordered the release of classified prewar intelligence about Iraq through Vice President Dick Cheney and Chief of Staff I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby to New York Times reporter Judith Miller in July 2003...

And the Obama Administration?

In 2010, NBC News reporter Michael Isikoff detailed similar secrecy machinations by the Obama administration, which leaked to Bob Woodward “a wealth of eye-popping details from a highly classified briefing” to President-elect Barack Obama two days after the November 2008 election. Among the disclosures to appear in Woodward’s book “Obama’s Wars” were, Isikoff wrote, “the code names of previously unknown NSA programs, the existence of a clandestine paramilitary army run by the CIA in Afghanistan, and details of a secret Chinese cyberpenetration of Obama and John McCain campaign computers.”

The secrets shared with Woodward were so delicate Obama transition chief John Podesta was barred from attendance at the briefing, which was conducted inside a windowless, secure room known as a Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility, or “SCIF.” Isikoff asked, quite logically, how the Obama administration could pursue a double standard in which it prosecuted mid-level bureaucrats and military officers for their leaks to the press but allowed administration officials to dispense bigger secrets to Woodward.

And "in 2012, as the presidential campaigns gathered speed, after the New York Times published stories about classified programs, including the 'kill list,' the drone program, details about the Osama bin Laden raid, and Stuxnet, all considered successes by the administration. The reports infuriated Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), who essentially accused the Obama White House of leaking these top secrets for political gain."

The final category of leak that Shafer chronicles is perhaps closest of all to what Edward Snowden did, and if you read to the excerpt's end I fully agree with its conclusion:

Sometimes when policy debates get driven underground by secrecy, members of the governing elite band together and tell their story to the press. The most recent example of this banding would be the 2005 storiesin the New York Times about a previous secret NSA surveillance program. The Times series by James Risen and Eric Lichtblau enraged the Bush White House, but there nobody was charged with leaking because the series portrayed itself (accurately, I would guess) as the product of intense, internal government dissent. As Risen and Lichtblau wrote, nearly “a dozen current and former officials” spoke to the paper anonymously about the program “because of their concerns about the operation’s legality and oversight.”

The willingness of the government to punish leakers is inversely proportional to the leakers’ rank and status, which is bad news for someone so lacking in those attributes as Edward Snowden. But as the Snowden prosecution commences, we should question his selective prosecution. Let’s ask, as Isikoff did of the Obama administration officials who leaked to Woodward, why Snowden is singled out for punishment when he’s essentially done what the insider dissenters did when they spoke with Risen and Lichtblau in 2005 about an invasive NSA program. He deserves the same justice and the same punishment they received.

Leaks of classified information in the United States will remain common, regardless of what happens to Snowden, because they frequently serve the interests of people in power—and they won't be prosecuted precisely because they are powerful or connected. That longstanding, bipartisan dynamic is far more important to the norms surrounding official secrets in the U.S. than how a singular, unrepeatable, once-in-a-generation leak is handled. And even if Obama buckled to New York Times pressure and pardoned Snowden tomorrow, would-be leakers couldn't help but be aware that he's also waged an unprecedented war on whistleblowers that preceded the Snowden leaks (even though neither the unjustly persecuted Thomas Drake nor any of the others has done any real harm to U.S. national security.)

The case for forgiving Snowden is strong. And the costs of doing so are wildly exaggerated. For apparently altruistic reasons, Snowden revealed scandalous instances of illegal behavior, and the scandal that mass surveillance on innocents is considered moral and legal by the national-security state, though it knew enough to keep that a secret. It is difficult to imagine another leak exposing policies so dangerous to a free society or state secrets so antithetical to representative government. The danger of a Snowden pardon creating a norm is virtually nonexistent.